antichamber review: flipping the script on learning in video games

Over the past few days, I’ve spent many hours wandering the corridors and exploring the rooms of Antichamber, the 2013 puzzle platformer game by Alexander Bruce. It’s a mind-bending experience packed with tons of intriguing puzzles, and aside from some bugs and initial confusion, the game has really grown on me.

If you’ve haven’t played Antichamber, here’s the game’s brief description on Steam:

Antichamber is a mind-bending psychological exploration game where nothing can be taken for granted. Discover an Escher-like world where hallways wrap around upon each other, spaces reconfigure themselves, and accomplishing the impossible may just be the only way forward.

Reviews of Antichamber inevitably bring up comparisons to the Portal games – it is similar in structure, and even has its own “gun” device. In the end, the immense popularity of the Portal series drowned out much public awareness of the smaller, indie, less graphically pretty Antichamber, which was released in the shadow of 2011’s Portal 2.

PC Gamer’s review begins:

Unlike Portal, there’s no test-subject narrative behind Antichamber, an austerely intellectual first-person puzzler…1

While the puzzles were praised, critics often seemed to think that the minimalistic style meant that the game lacked narrative, personality or meaning.

IGN’s review says:

Antichamber lacks personality and its narrative feels pointless, but its puzzles are expertly crafted and wonderfully inventive challenges. … The plot and ending of Antichamber are vague and inconsequential, and it’s not doing a whole lot with its visuals to tell a story, either.2

Contrary to these reviews, I’ve actually found that Antichamber is surprisingly deep in story for a puzzle game. This comes down to how the game is designed for learning.

Games are Linked to Learning

Since I read Raph Koster’s A Theory of Fun for Game Design, I’ve been looking for a way to write about the thesis that games are about learning. Koster claims that all games are on some level “edutainment”, and that fun is intrinsically linked to learning. Once players stop learning in a game, he says, it stops being fun, and they stop playing it.

Games serve as very fundamental and powerful learning tools… Fun is learning in a context where there is no pressure.3

In truth, dissecting any well-designed game can provide evidence of learning, but no game I’ve found so far has illustrated this as well as Antichamber.

When thinking about learning in games, of course, there’s a propensity to lean towards puzzle games. And yes, the Portals and Mysts and Witnesses of the world show us how you have to learn about a game’s systems and rules and apply that knowledge in order to proceed further.

But there’s something in Antichamber‘s design that makes it unique in its approach to learning.

Antichamber Subverts how Games Usually Approach Learning

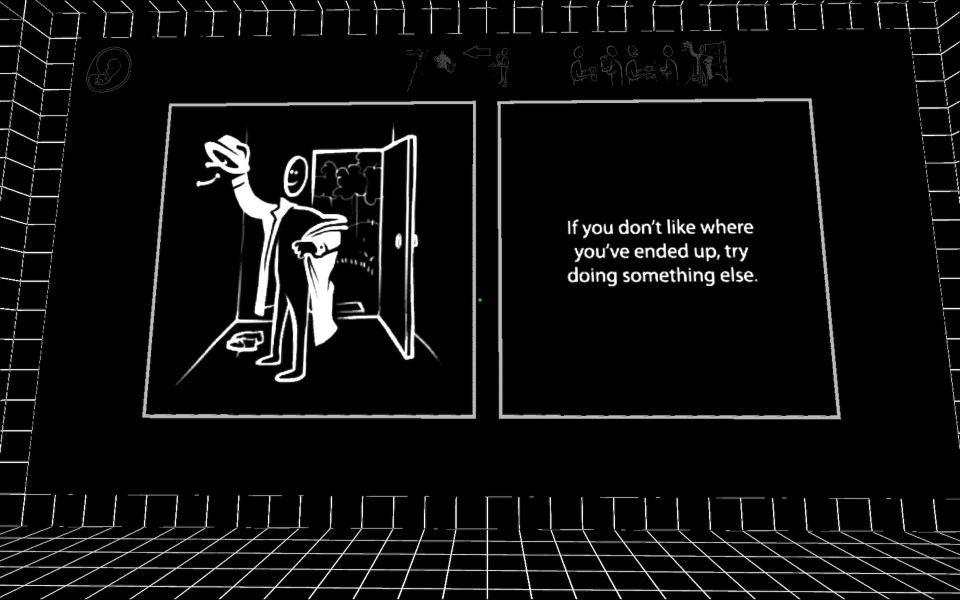

Other than the puzzles, the only distinctive feature of Antichamber‘s environment is a series of black and white signs. Each sign has an image on it, and when clicked, displays a short snippet of helpful text.

For the first hour or so, I viewed these signs as directions or helpful hints. When I saw a sign that read, “Some paths are straight forward”, I would try to go forward to find a new area. In fact, signs like these are common in games, from the signposts in Zelda or Pokemon or even Portal that give you hints about which way to go next, or the popups, tooltips and UI indicators in countless more games that are specifically placed to help players out when they are stuck.

In Antichamber, however, the signs did not seem to help. After a while, I got frustrated because it seemed like I was encountering the signs out of order, after I’d already done the thing they hinted to me about. “Building a bridge can get you over a problem” appeared after I’d already built a bridge to get me across a chasm. And I’d think, “well thanks for nothing, I’ve just figured that out.” Maybe I’d approached the problem in the wrong order, or from the wrong direction. I must have been meant to build the bridge from the other side, the side with the sign there to give me this hint when I was stuck.

That’s how games work, right? Well, not this one.

When I finally realised that the signs tell you what you’ve already done, in fact, what you’ve accomplished in the puzzle you’ve just solved, it was a revelation as sweet as solving the many complex puzzles in Antichamber itself. With this genius design move of putting the sign after the puzzle, showing you what you’ve learned, Antichamber hammers home the concept that games are about learning.

The signs weren’t hints after all. They were lessons.

Learning and Antichamber‘s “Moral Wall”

A subtle difference in where those signs were placed, before or after the puzzle, makes Antichamber stand out amongst legions of other games. It’s a knowing nod to the concept of games as tools for learning, a self-awareness unlike any other game I’ve played.

The signs went from being frustrating to being encouraging. They reinforced the concept that you learn by exploring, and experimenting, and most of all, you learn by doing the thing. They made me want to try and solve more puzzles by exploring, experimenting and doing.

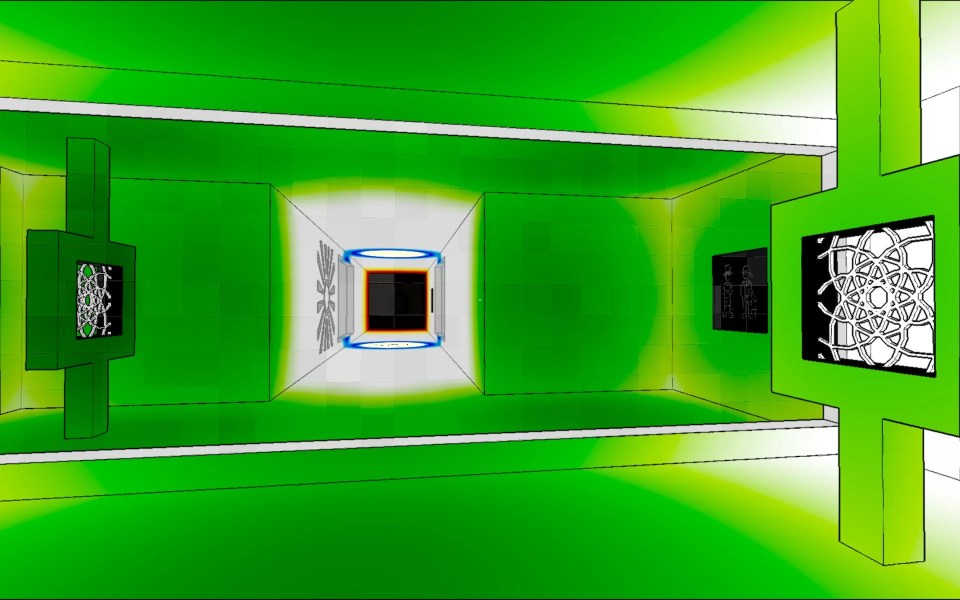

One wall of the main room is dedicated to collecting these signs as you encounter them throughout the game. At first, I thought it was some way of gathering the hints in one place to help you solve future puzzles – and it is – but as I realised that the signs weren’t hints when I’d discovered them, the wall took on another meaning.

The wall was now a record of all the challenges I’d triumphed over, a virtual scrapbook and reminder of all the things I’d learned and all the places I’d been. Later, I found out what it’s called, not “Collection of Signs” or “Appendix of Game Hints” but of course, the “Moral Wall”.

How Antichamber Delivers on Both Puzzle and Story in its Game Design

This brings me back to my opinion on Antichamber‘s story.

Raph Koster also writes that games aren’t like stories, and don’t usually have morals or themes. He goes on to say that it’s difficult to make games with good stories.

I can’t deny, however, that stories and games teach really different things. Games don’t usually have a moral. They don’t have a theme in the sense that a novel has a theme. … It’s easier to construct a story with multiple possible interpretations than it is to construct a game with the same characteristics. However, most games melded with stories tend to be Frankenstein monsters. Players tend to either skip the story or skip the game.3

Antichamber is different from most games. The excellence in Antichamber‘s storytelling is that you can’t skip the story if you play the game. This is because the story of Antichamber is the story of what is happening to you, the player. It’s about you solving the puzzles and learning things and gathering experiences in the game but also in your life.

There’s no superficial layer of sarcastic comments like those from GLaDOS in Portal, nor world-building audio tape recordings of philosophical quotes like those in The Witness. And thus, the narrative is more poignant than Portal‘s test-subject storyline, or The Witness‘ island research facility mystery.

The story of Antichamber is what you have chosen to do with your time – play the game. It’s highlighted by the clock that counts down in the main room, giving you an hour and a half of “time remaining” and then allowing you to continue past that time, by presenting you with the lesson that reads, “Live on your own watch, not on someone else’s.”

Antichamber is a Game about Life

There is a swinging pendulum in one of the first rooms I found in Antichamber. It swings across four letters one at a time, and if you’re patient enough to stand and wait you’ll see it spells out “LIFE”.

This game is about learning. And this game is about life. Life, it asserts, is a series of challenges, experiences that you can overcome with your perseverance and skill from which you can gain insight and learn lessons.

Fittingly, Antichamber gives you the morals the same way life hands them to you, after you’ve experienced it.

Experience is a hard teacher because she gives the test first, the lesson afterward.

— Vernon Sanders Law

The first lesson, by the way, shows up as the first sign on the Moral Wall when you arrive at the main room, before you enter the puzzle rooms. “Every journey is a series of choices,” it reads. “The first is to begin the journey.” I initially thought that it was telling me to start the game, but looking back with fresh eyes, I now realise I had already started the game before that lesson was presented to me.

Antichamber opens with an illustration of a fetus alongside this lesson, and closes with… well, you’re going to have to play it to get the lesson afterwards.

References Cited

- Valjalo, David. “Antichamber Review.” Reviews. PCGamer, 31 January 2013. Web. 5 July 2020.

- IGN. “Antichamber Review.” IGN, 31 January 2013. Web. 5 July 2020.

- Koster, Raph. A Theory of Fun for Game Design. Arizona, Paraglyph Press, Inc., 2005.